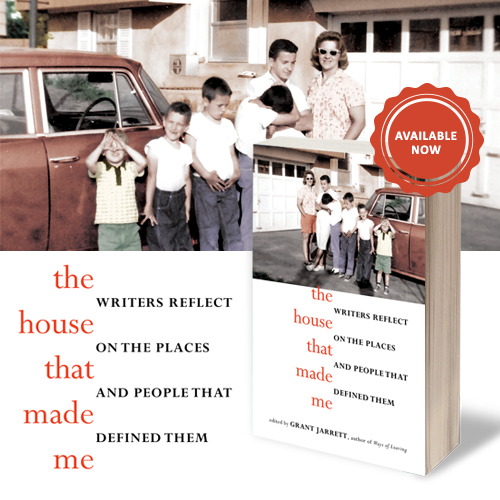

from The House That Made Me: Writers Reflect on the Places and People that Defined Them. Available on Amazon.

Edited by Grant Jarrett. Spark Press, 2016

This short essay about life in the apartment where I grew up in New York City inspired my work for Eva and Eve. I allowed myself to drift back to the past and recall the sensory memories of my childhood, painful and wondrous. What did your childhood look like, or smell like?

It’s my building, the one I grew up in, incorrectly numbered on tree-lined West End Avenue, Manhattan, New York City, USA, Google Earth. This was my mother’s adopted neighborhood, just down the street from the apartment where she lived with her parents shortly after their flight from Nazi-occupied Vienna in 1940. German and Yiddish were spoken on these streets then, and in so many apartments where Jewish refugees had found sanctuary. My father, a Philadelphian, child of Russian immigrants who fled a previous wave of anti-Semitic persecution in the Ukraine, met my mother on a blind date in 1947 and happily left his own city for life in Manhattan. He and my mother moved to this building when I was a year old, having outgrown their one-bedroom apartment down the street.

Elegant green canopy outside, installed after I left for college when gentrification moved uptown in a hurry, evicting the residents of the single room occupancy hotels on the side streets, loitering impatiently until folks in rent-controlled apartments croaked or moved to Brooklyn or fled to the suburbs. Above the canopy, a pre-war apartment building of fifteen floors (superstitiously skipping unlucky 13), with a white façade at street level, brown brick above, every pore of baked clay infused with decades of city soot and grime. The fifth floor has the sweet Juliet terraces, too small to use, even to gaze at the inconstant moon. The architect’s style is some 1920s mash-up of 19th century grandeur by way of Medieval Castle Revival. When I count up to the sixth floor I see the air conditioning units in my father’s apartment windows. More recent apartment co-op buyers have installed central air. The satellite photo shows bright yellow compactors and street pavers parked in front of the building in the sparse shade of young trees. What a racket that must have made as workers jack-hammered and removed street asphalt to replace a section of water pipe or sewer, layer upon layer, excavating the hidden cobblestones that once paved the avenue. I recall my dad and his wife complaining bitterly about the noise. Spring, summer, or autumn in New York City is always about street work, your block or a neighbor’s, ancient infrastructure in a continuous state of near collapse.

West End Avenue, my home. Rumble of cars on well-worn granite cobblestones is the continuous white noise background to our lives. An opera singer rehearses in her apartment across the avenue, her scales and arias trilling into our open windows—ah-ah-ah-AH-ah-ah-ah!—rancid perfume of uncollected trash wafts upward from the back courtyard in summer—Ah-ah-ah-AH-ah-ah-ah!—honking horns on Broadway, one avenue over, where my mother shops at Sloan’s and the green grocer and Harry, the German butcher, one of the only times I hear her speak her first language. When fire trucks race down the avenue with sirens blaring, my younger brother Simon is nearly desperate with excitement, pressing his hands and freckled nose against the windowpanes for a better look. Don’t! My mother shouts for the umpteenth time. Don’t lean on the window! Summertime, hair damp from the playground sprinklers in Riverside Park, where under the watchful eye of Hortense, our babysitter, Simon and I strip down to our white underwear and run through the cold spray. The old ladies sitting outside in folding chairs never fail to squish our cheeks when we return, especially paying special attention to Simon, with his dark curls and thick glasses. I hate being close to the ladiesThese crinkly ladies who suffocate us with hair spray, talcum powder, and rose perfume. In winter Hortense waits for us outside the building as we are released from the school bus, bundled in swishing jackets and snowpants, mitten strings tugging and rubbing inside our sleeves.

Through heavy glass doors, up the stairs into the dimly lit lobby, where handsome Victor and portly Albert stand sentry in their gray uniforms, sorting the mail. Dark carved wood chairs in the lobby we aren’t allowed to sit in and creak when we do. Off to the right, the ornate wood-paneled manual elevator for our side of the building. If no one else is going upstairs, Victor lets us work the polished brass lever up to the sixth floor. Our apartment is on the right side as you step out of the elevator. The lock is tricky—you have to jiggle the keys just so. Inside, our hallway is dark, lined with bookshelves, and the parquet floors creak spooky-like.

Two bedrooms, each with white-tiled bathrooms. A maid’s room, big enough for a twin bed for when Hortense sleeps over. L-shaped kitchen, painted shiny marigold yellow, my mother’s domain when the lights are on. Cockroaches rule at night. She grunts as she smushes them with her bare palm if she goes in there after the dishes are done. My dad uses the dining room as his artist’s studio. We can watch him through the glass doors but we aren’t supposed to disturb him. He listens to music while he works, or sometimes a baseball game. Hhe uses clam shells we find in Maine for his paint palettes. The living room is furnished with low couch, coffee table, credenza, dining table and chairs. It is a room rarely used, except when my parents host dinner parties and the hours I spend after school doing battle with the upright piano. A series of Japanese woodcut prints hangs on the wall: landscapes of mountains, figures in pointed hats hurrying across a bridge in the rain. One is of a Samurai warrior dressed in an ornate black robe, wielding a sword against an unseen enemy, a fearsome companion who stares me down as I practice.

The two bedrooms face West End Avenue. My brother and I share one of them. The wood floor is covered with black and white speckled linoleum where we pile our stacks of wooden blocks, Lego creations and race Simon’s Matchbox cars. Our twin beds are on opposite sides of the room. In the middle is a low round table set under the overhead light where we draw pictures, play board games, or arrange tea parties for stuffed animals and my dress-up dolls. We are not allowed to play in the hallway, we are not allowed to throw balls or jump around. But the room is our place, where I am mostly the boss of our games. Until Simon whacks me with a school book bag because he is tired of me being the boss. Until my mother stands in the doorway and says clean up this room right now, and then the magic force field is gone and it’s time for dinner.

My mother works in midtown at the same publishing company as my father. We only get to visit their office on school vacations. They come home from work on the Riverside Drive bus at 6 o’clock, after Underdog and Rocky & Bullwinkle. We watch them on the black and white Zenith in our room. When my parents get home, my father changes out of his suit and shirt and tie and goes to his painting studio. My mother makes dinner. The best is when she takes out the electric pan, which means we are having fried chicken. If she is making liver I nearly want to puke from the smell, but we have to eat everything because there are children starving in Biafra. Sometimes I can hide bits in a napkin and then throw them away when no one is looking. My mother is tired, so that helps. She irons my dad’s shirts after dinner while we go back to our room for a bath and bedtime.

The room changes at night, even when we are still awake. Sometimes we listen to a man telling a Just-So Story on our record player, in a rich voice I recognize from the Christmastime Grinch movie, while we look at the pictures in our book. I know the pictures by heart. I lie in bed mulling over the Elephant’s Child’s ‘satiable curtiosity and the Parsee’s cake that made the rhinoceros’s skin itch into wrinkles until my parents turn out the overhead light and say goodnight. There is still plenty of light from the outside world—the street lights on West End Avenue and the car headlights flashing beams across our ceiling, and always that rumbling, like approaching ocean waves, louder and louder till they pass under our window, then quiet again until the next one passes. The room is an island surrounded by waves, and then it is three small islands—my brother and me in our beds, and the smaller island of the round table under the ceiling light where my mother puts The Vaporizor—a machine that looks like a sightless white duck with a curved bill—that blows out cold mist at night so my brother can breathe better. The Vaporizor shushes other sounds, like my parents getting ready for bed in the other room, but it can never shush the waves outside our window, even in the winter.

I wake in the night. The black-robed samurai warrior wielding his sword flies away into his white paper world, but I am all sweaty, wedged between teddy bear and dolls. A car rumbles down the avenue, then the street is quiet, just the hum of the Vaporizer. The three white glass globes of the ceiling light stare down at me. I never noticed that the globes form the triangle of a face, milky eyes and gaping mouth, and I never noticed the wispy aura around the globes. I get out of bed and tiptoe over to The Vaporizer, placing my hands in front of its open mouth to feel the cool mist. I close my eyes and put my face into the blast of damp wind. It’s like the seaspray mist kicked up by the passenger ferry we take to the Maine island in the summer. If I keep my eyes closed I can pretend I’m there. When I open them again and look up the white globes are still staring at me, expressionless but menacing, like the empty eye sockets of a skull. I scurry back to bed and burrow under the sheets and blankets. Teddy and dolls will guard my island. It’s hot and airless under the covers. I worry that I might suffocate. I slide just the top of my head into the night air, keeping my eyes squeezed shut. When I peek, the lamp is still staring down at me. Maybe it isn’t fair to make Teddy and dolls do all the work. I pull them under the covers and slide the rest of my head out. I will stand guard. I will defend my island against all invaders, including Samurai warriors and the ghost in the overhead lamp. I fold an arm across my closed eyes so that I won’t be tempted to look up at the face above me.

I wake in the morning with my arm still across my eyes, stiff and numb as if it doesn’t belong to my body at all. The arm wakes up tingling with pins and needles and then it becomes my arm again. The room is my room, my brother is across the room in his bed. Classical music is playing loudly on the radio in the hall. I can smell toast burning in the kitchen. Another school day.

My eye scans down the building to the street, and the yellow construction equipment parked in front of the building. I wonder how often the photos change. Next time the satellite passes by, the yellow equipment will be gone and the street will look as it does when I visit my father, now 90, and his second wife. Victor and Albert are long gone, but there is still one doorman, Jose, who smiles with recognition when I walk into the lobby, still ersatz Medieval, the wooden lobby chairs replaced with contemporary designs. The manual elevator is automatic, the original wood interior refinished and gleaming. Upstairs, my father and his wife serve us lunch in the living room, rearranged and brightened since my mother’s death almost ten years ago. The floors are sanded and varnished a pale oak, the walls are white instead of maroon. Even the marigold yellow kitchen is now white. The roaches have been beaten back. A new table has replaced the Formica one my mother used to prepare and serve our meals. My father’s wife uses the bedroom my brother and I shared as an office, with the same ceiling fixture. The paned windows have been replaced with airtight single pane modernity. I greet the Samurai warrior in the living room. Every time I visit, my father and his wife ask me to take away something—dishes, silverware, books. They are lightening their load.

Sometimes I pace these rooms where I played as a child and brooded as an adolescent, looking for objects I know are long gone—our play table and chairs, The Vaporizer. I open the closet in my old bedroom half expecting to see a familiar coat or dress. Sometimes I scan the rooms with the appraising eye of an eager real estate agent, wondering who will live here next. Not me again, I am sure of that, not in these six rooms. Classic Six Co-op in elegant prewar building, Upper West Side. All new windows, EIK, original parquet floors, bathrooms, and period details, near great public schools, Riverside Park, shopping, transportation. Bring your architect and make it your own! I snap back quickly to my present comfort—that my father can live his remaining years here with his books and music and art. In his bedroom I visit with the photos of my mother perched on the dresser. I think she would like the changes my dad and his wife have made, though she didn’t embrace change as a rule. Before I leave, I peek out the window to West End Avenue and draw a finger through the fine layer of city dust settled on the windowsill, pressing the black pigment between my fingers like a balm.